It’s important when making the decision to homeschool that you set healthy boundaries for your schooling with your family. You don’t want school to take over your life and home, but on the flip side you want to make sure you’re spending quality time on school. It’s not always an easy balance.

We’re fairly new to homeschooling, compared to many families, and our family is in a continual process finding the balance and boundaries of Montessori homeschooling.

Make a Decision to Homeschool

The first, and most basic, boundary in homeschooling is to make a decision to homeschool. It could be rough on the children to school traditionally, and also come home to more school. Although this is a decision for each family to make on their own. Depending on where you live, the make up and age of your children, and the opportunities available this may be the best decision for your family.

The second and, I believe, most important boundary is to decide as a couple to homeschool. Without the support of your spouse, homeschooling could be a lonely and exasperating venture. It’s good to have someone to bounce ideas off, give you a different perspective, and help make the educational decisions for your children.

What if my spouse disagrees with the idea to homeschool?

Share how you feel, why you think it is a good idea, and weigh the pros and cons together. Perhaps they will begin to see it from your perspective; if not, then maybe you can approach the topic at a later time or ask how they’d feel about incorporating portions of the philosophy into your home life.

Talk about Your Ideal Homeschool Environment

Before you start buying materials and planning lessons, set aside time to dream up your ideal homeschool environment. While few families will be able to have their dream homeschool room when they start schooling, it’s good to brainstorm what you’d like and work toward that in baby steps.

It could be you want an entire room dedicated to schooling, you could consider having children share a bedroom and using the third as a homeschool room. Or if you’d like to have quick access to outside, perhaps planning your schooling area near a backdoor or sliding glass door would work for your family.

Aside from the physical environment, consider the emotional, spiritual, and mental environment you want to create. For me, I want our children to have a natural yearning for learning, to ask questions, and continue to find the world fascinating. I want to say “yes” far more than I say “no,” which is a struggle for me as a recovering perfectionist. I often want things to go right and stick to the plan, but knowing my boys they learn best by adventure and discovery.

As I said in Creating a Montessori Environment Without Losing the Home,

“I want them to feel empowered by their education. […but] I never want to hold so tightly onto the philosophy at the expense of losing our home environment.”

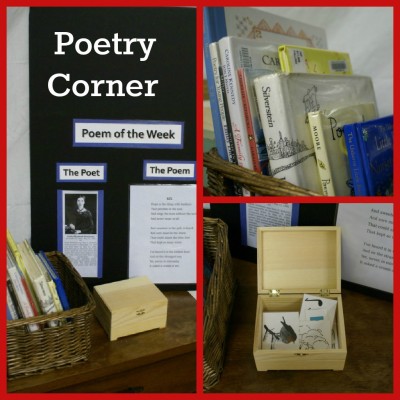

Designate a Place to School

Decide what area in your home you want to be homeschooling headquarters. The kitchen table? The living room? Maybe a combination of the two? The homeschool room in your walk-out basement (that’s my dream)?

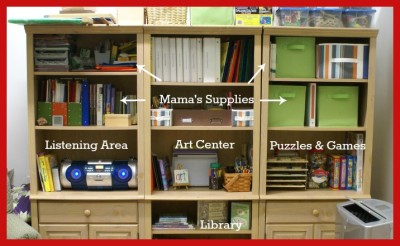

We homeschool in our family room, which is now dubbed as the school room. It’s the center room in our house, connecting the kitchen and living room on one side and the hallway to the bedrooms on the other. We use our old dining table for school even though it’s not quite Montessori because of its height, but we’re small on space so we use what works.

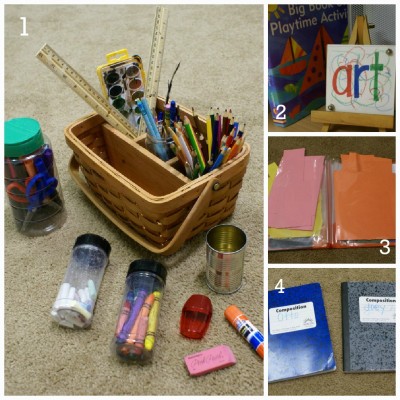

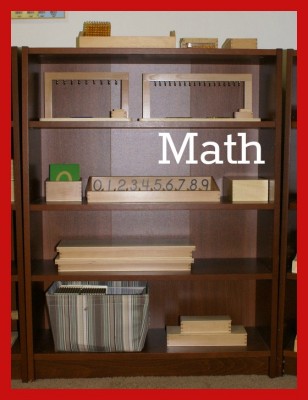

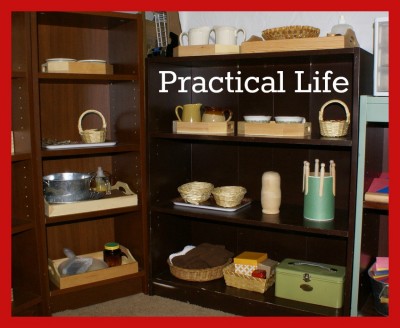

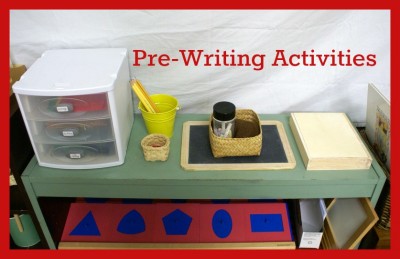

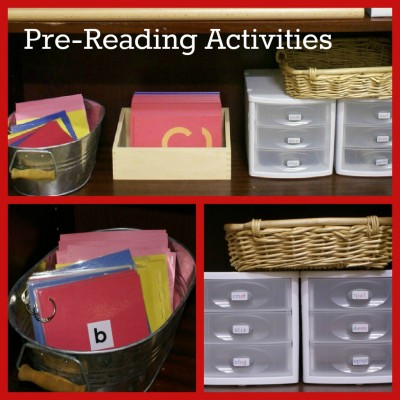

A few years ago we invested in four IKEA Billy bookcases (the short one’s) for the school room. I’m not able to have all the materials I’d like out, which means trying to stay on top of rotating the works. We have a shelf for art supplies and our metal inset trays, as well as a nature table I’m currently working on to be more interactive, rather than just decorated.

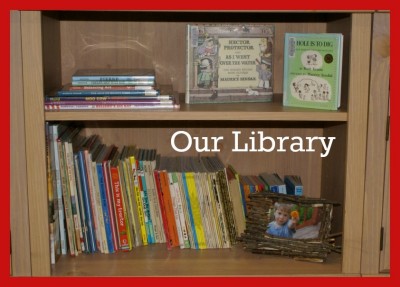

One caution I’d give is to avoid homeschooling in children’s bedrooms. Those, I feel, should be a place of relaxation, retreat, and play. I keep Montessori materials out of the bedroom, in part to keep tabs on all the pieces, but also so their room is school free. Games, puzzles, and books cross back and forth freely. 🙂

Decide on Materials & Budget

We want the best education for our children, but we also need to consider the monetary investment of homeschooling. An important boundary is deciding how much money to designate for homeschool costs and where in the budget will it come from. Maybe you’ll have to cut back in a few areas to have a regular homeschool budget. You may also want to consider asking for Montessori materials for Christmas and birthday presents or making your own materials.

Homeschool Routine

Finding a homeschool routine that fits your family may take time, but is essential. We’re still trying to find a good rhythm.

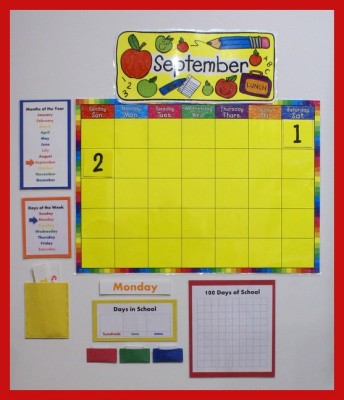

It might be helpful to outline what your ideal homeschool day would look like–what time will you start? Snack time? Reading time? Work period? Music and Art? Think of the things you want to include in your day and draft them out in 30-minute to an hour blocks (or what works best for you and your children).

Try the schedule and see if it works. What hiccups were there? What worked really well? What did the children respond to? Was it too early to start? Evaluate and and draft again.

I think we’re finally coming into a routine that works well for us. We usually school Monday – Friday from 9am – 11:30am. I’d like to start at 8:30 to have a 3-hour work period, but it’s something to work toward. We finish by 11:30, so I have time to prep lunch.

Consistency is key. Try to keep the same routines every day you homeschool, whether you school Monday – Friday or Monday, Wedensday, and Friday. It helps the children to know what to expect and be prepared for the day. I also like to tell the kids what’s going to happen for the day at breakfast, whether we have someone visiting, we’re running an errand, or have a special project.

Make Family a Priority

Don’t let school drive your family. If you’re in school mode from sun-up to sun down, it might be time to step back and evaluate how you approach homeschooling. While some of this may vary on your child’s age and level in school, your home needs to be a home first and a school second. We should aim to be the mother (or father) first and teacher second.

We strive to find a balance with the role as teacher and parent. We shouldn’t hold a child’s bad attitude or poor work ethic during school over their head the entire day. Deal with it during school time and let it be. Let your children be free to be your child when school is over. (I’m preaching to myself here too.)

Keep family time a priority by sitting aside family game nights, special dinners or cooking activities, or outings.

Know When to Take a Break

There will be hours, days, or even weeks when you’ll feel exasperated, burnt out, or just plain out of ideas. Know it’s okay to take a break.

A break doesn’t mean you’re finished homeschooling forever, but that you’re self-aware enough to know you’ve stretched yourself thin and you need time off to be able to homeschool best and keep your family first. A break may be just a few days or perhaps a week.

It’s better to stop for an extended breather, than to run yourself into the ground, strain relationships within the family, and lose all momentum for homeschooling.

Regularly Evaluate Your Decision to Homeschool

At the end of each year, it’s good to evaluate your decision to homeschool. Is it working best for your family? Has your stage in life changed? Has a new job, family illness, or another major change affected your homeschooling? Are your children responding to schooling at home? Do they have special needs that might be attended best elsewhere?

It’s okay to stop homeschooling. It’s not the end all to be all and it’s not the magic bullet. It’ll only work best as far as it works for you.

***

Keeping healthy boundaries in homeschooling will be both a benefit to you and your children. It will add more peace and productivity to your family and homeschool environment. My family’s boundaries, routine, or school room may not be what works best for your family.

It’s a journey. We’re all learning, evaluating, and reassessing what works best for our family.

***

I’d love to hear your thoughts and what some of your boundaries are.

Updated, June 2014.